If you go down to the woods today you are sure of a big surprise – sinister figures riding around on quad-bikes. It is however for serious endeavour- not a picnic.

Now that the rutting season has finished, when stags accumulate their harem, the deer management process can commence. Ashridge in a statement say that they “carry out regular deer counts which indicate numbers of around one thousand five hundred to one thousand eight hundred deer being present on the estate at any one time – the number varies as it is a wild herd rather than a captive one. The fallow deer cull target for 2017 will be around six hundred and fifty, with muntjac which are particularly damaging to low growing flora, taken out in small numbers. Cull targets are based upon the assessment of damage being done, rather than the deer numbers – predation of the under-story resulting in a lack of tree regeneration and the loss of rare flora and bird nesting habitat”.

It is an unusual event these days to report on an abundance of wildlife but the fact is that there are too many deer at Ashridge, causing untold damage.

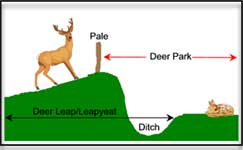

The Normans introduced the first fallow deer in the 11th Century to their park at Frithsden ( Le Frith). Medieval deer parks were of Royal patronage, used for hunting with very strict rules governing their control. Henry VIII no doubt used Ashridge for that purpose, although there are no records to confirm this. The first record of deer in the park at Ashridge was in 1681 when a certain Thomas Baskerville paid a visit and mentioned a separate park for red deer and one for fallow deer. The parks were not enclosed until some time after 1610, but a survey by Cave in 1721 shows one large enclosed park. When Peter Kalm the Swedish botanist visited the area in 1748 he noted that there were about one thousand deer in the Park, and some of them were pure white. Ash trees were laid down for them to gnaw the bark and sheds were erected throughout the Park for their protection in bad weather. The Park was enclosed by a fence or “paling” of wood, built on a bank to contain the deer. A “deer-leap” was introduced in the fence which enabled deer from outside to jump into the Park but prevented them from escaping. At this time deer parks were mainly kept as a sign of wealth and position in society, when the herds were culled for their meat, and skin. In 1903 two visitors reported that the Park held herds of red, fallow and Sika deer as well as St Kilda sheep and Angora goats. Prior to the sale of the Estate in the 1920s the red and the fallow were to be sold. For the red this was reasonably successful and a number were taken to Richmond Park. However, before the fallow catch-up could be organised, much of the deer park fencing had collapsed and many of the deer escaped into the surrounding countryside and formed the basis of the herd we see today. In 1928 the Agent for the Estate reported that, apart from the escapees, there were about one hundred red, two hundred fallow and twenty sika in the Park and shortly afterwards the National Trust decided that the red should be eliminated, as they were thought to be a danger to the public.

The remaining deer fencing was then removed and the fallow were allowed to go free. The number of the remaining fallow deer fluctuated over the years from a low point of one hundred and eighty in 1972 when one hundred were culled each year.

The ghostly figures out there are highly qualified professionals, required to wear an identifying arm-band and are strictly controlled, so have no fear when entering out for a walk in the woods – but remember to wear a high visibility Ashridge jacket.